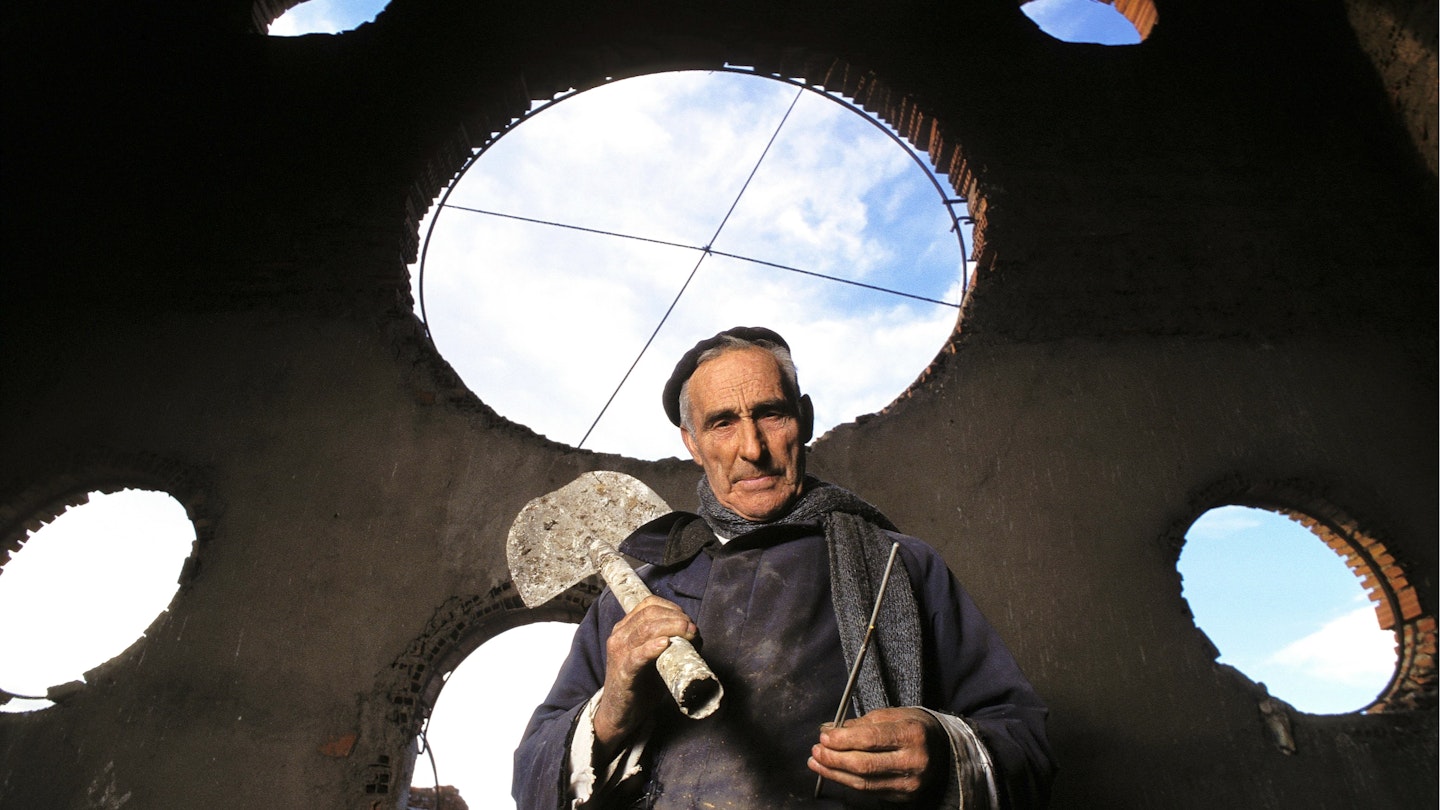

Justo Gallego Martínez, a former monk, has spent 60 years building a cathedral in the outskirts of the Spanish capital out of anything he can find. Until recently, its future seemed bleak.

Editor's Note: On November 28, 2021, six days after this piece was published, Spanish press reported that Justo Gallego Martínez had died at the age of 96.

Towering over a nondescript Madrid suburb, the Cathedral of Justo Gallego is a vision in broken brick, colored glass and concrete. Made from mostly salvaged materials, the 4700-square-meter (50,590-square-foot) building is the life’s work of an ex-monk who constructed it almost single-handedly without plans or permission. Though visitors come in droves to marvel at the building, the authorities have studiously ignored its existence, with neither the town council of Mejorada del Campo nor the Catholic Church wanting to take responsibility for it.

For years, it seemed as if its creator, Justo Gallego Martínez, 96, would never be able to convince anybody powerful enough to take on the risks of a building many said was structurally unsound. In recent months, the situation looked especially dire. His health failing, Gallego took to his bed over a year ago, and rumors spread that the building might be headed toward demolition. But this summer, an NGO led by a maverick priest stepped in and called on a firm of structural engineers that has, to everyone’s surprise, declared the building safe.

A promise made

This isn’t the first time Gallego has stared death in the face. Back in 1961 he had to leave an order of Trappist monks after contracting tuberculosis. While struggling with his condition, Gallego prayed to the Virgin Mary, promising to build her a cathedral if she saved him. He recovered and immediately got to work, building on land he’d inherited from his family. At first, he scavenged bricks from old building sites, but as the project gathered momentum, locals began to lend a hand and to donate materials. Over time, Gallego grew to be an inspirational figure to the community of Mejorada del Campo. For many, the cathedral under construction for 60 years is a testament to the sheer resilience and creativity of the human spirit.

“He’s a marvelous person, he loves to talk to people, to explain everything. A wonderful person who loves Christ,” said Ángel López, 52, who has spent the last 24 years of his life beside his mentor, learning the construction techniques Gallego developed without any formal training.

Those who couldn’t give their time gave construction materials, including nearby factories and building sites who donated the cement used to reinforce the cathedral’s signature pillars made from stacked oil drums. Rising 35m (115ft), the cathedral complex includes a crypt, two cloisters, 12 towers, and 28 cupolas. Decorative elements make use of tires, ceramic shards, and empty metal cans. Broken bricks and exposed wire give the building’s high towers and wide staircases a raw aesthetic that celebrates the imperfections of its donated materials. Windows painstakingly made from tiny beads of smashed colored glass glued into the shape of sunbeams bathe the building in red and yellow light.

Still, not everybody is a fan of Gallego’s work. Comments made in 2013 by Andrés Cánovas, an architect at the Madrid School of Architecture, to online news outlet Madrilánea may have been responsible for the Church and the town council’s hesitancy to take on the project: “Any architect who signs off on this [building] would be crazy to do so,” Cánovas said. “I would never take my children to spend an afternoon there; it violates all safety regulations.”

Under new management

Before becoming bedridden, Gallego tried to bequeath the cathedral to the Catholic Church, but his donation was refused. He then passed the cathedral on to López, who was at a loss about how to deal with the authorities. López gifted the rather cumbersome inheritance to Mensajeros de la Paz (Messengers of Peace), a Catholic NGO that works with Madrid’s unhoused population. When things were made official this summer, the organization wasted little time commissioning a survey from Calter, an engineering firm that has worked on high-profile projects, such as Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu stadium.

The news that the firm had declared the building structurally sound was announced in the Spanish press on November 9. Though Gallego was unavailable to comment, those close to him affirm that he is delighted with the news that, barring four cupolas that were demolished the week before last, Calter looks ready to sign off on the building.

“It is incredible that they built a cathedral of this scale without blueprints nor an overall design, and that this was done by a single individual,” Calter’s construction manager, Jesús Jiménez, said in an article in El Mundo.

The next step forward is for the town council’s technical team to approve the building. But things look positive. The municipality of Mejorada del Campo seems to be keen on expediting matters and is, at the same time, filing a petition to get the building declared Bien de Interés Cultural (an asset of cultural interest) by the Community of Madrid.

Father Ángel García Rodríguez, founder and president of the Mensajeros de la Paz, is confident that Calter together with the town council will officially sign off on the building by Christmas, when he hopes to put on a concert to celebrate.

López, however, rushing to complete work to cover cupolas that are open to the elements, is more circumspect.

“At the moment we are at a standstill; let’s see if we get the permits,” said López.

One thing for certain is that officials from the Catholic Church will not be attending any event in the cathedral, with the Archdiocese of Madrid still refusing to visit despite repeated invitations.

“They pretty much ignore us,” López said. “Well, now I have Mensajeros de la Paz.”

When asked how he feels about the cathedral not being consecrated by his church, Father Ángel dodges the question a little, pointing out that Mejorada del Campo falls within the diocese of Alcalá de Henares. “Usually, only one church in a diocese can be ranked as a cathedral, and Alcalá de Henares already has its own [cathedral],” he said.

A more certain future

Putting a positive spin on matters, Father Ángel has decided to make Gallego’s cathedral an inclusive space: “It’s not going to be a normal cathedral. Instead, it’ll be a place for men and women to gather. Those who believe and those who don’t will be able to come in. As it’s not a normal cathedral, the bishop won’t be involved.”

Famous for opening the doors of his church to those in need and for running a restaurant offering the unhoused a dignified dining experience, Father Ángel is a well-known figure in Spain. With his media savvy, many think he is exactly the sort of person the cathedral needs as a champion and, in general, locals are delighted that Father Ángel’s group has saved the building.

“We are very happy for the cathedral,” said David Rodríguez Valdepeñas, owner of Hi Da, a bar and restaurant that is around the corner from the cathedral. “It seems that they can continue with its construction and finish it off. That’s good, it strikes me as the right thing to do.’

While most of the chatter on social media seems to support Valdepeñas’ view, some expressed fears that Mensajeros de la Paz might begin to use the cathedral as a cash cow by charging entry. However, Celia Benito, the press officer for Mensajeros de la Paz, unequivocally denied these accusations and insisted that visitors will, as before, only be asked to donate what they can.

Since the news about the cathedral’s future broke, donations have indeed been pouring in: “Many people are arriving with building material, with materials for windows, even offers for heating or air-conditioning,” said Father Ángel.

Father Ángel also confirmed that Coca-Cola has committed to funding some of the construction work and in exchange, a huge portrait of Gallego done in Coca-Cola bottle caps has been mounted on the wall in the nave. The company has a long history with the cathedral. In 2005, an advertisement for a Coca-Cola sports drink, Aquarius, showed Gallego working on the building, attracting even more visitors to the site.

Even if they do raise the money needed to complete the cathedral, López is reluctant to commit to a completion date. More optimistic, Father Ángel hopes to finish things within three years. Whether Gallego will live to see that happen is uncertain — as is his final resting place. Besides securing the future of the building, his last wish is to be buried in the cathedral’s crypt. Though the local council is now on board with the effort to preserve the building, they remain unmovable on this issue, denying Gallego the right to be buried on the premises.

Ever the optimist, Father Ángel insists that this is not a big sticking point. “It depends on [getting] the permissions and on the authorities,” he said. “However, there is his spirit. When we die the only thing that remains is the spirit. His spirit will continue to reside there. It won’t be buried; it will be floating around the cathedral.”

You might also like:

Madrid vs Barcelona: which city is better?

5 stunning hikes near Madrid

Madrid's best parks for sightseeing